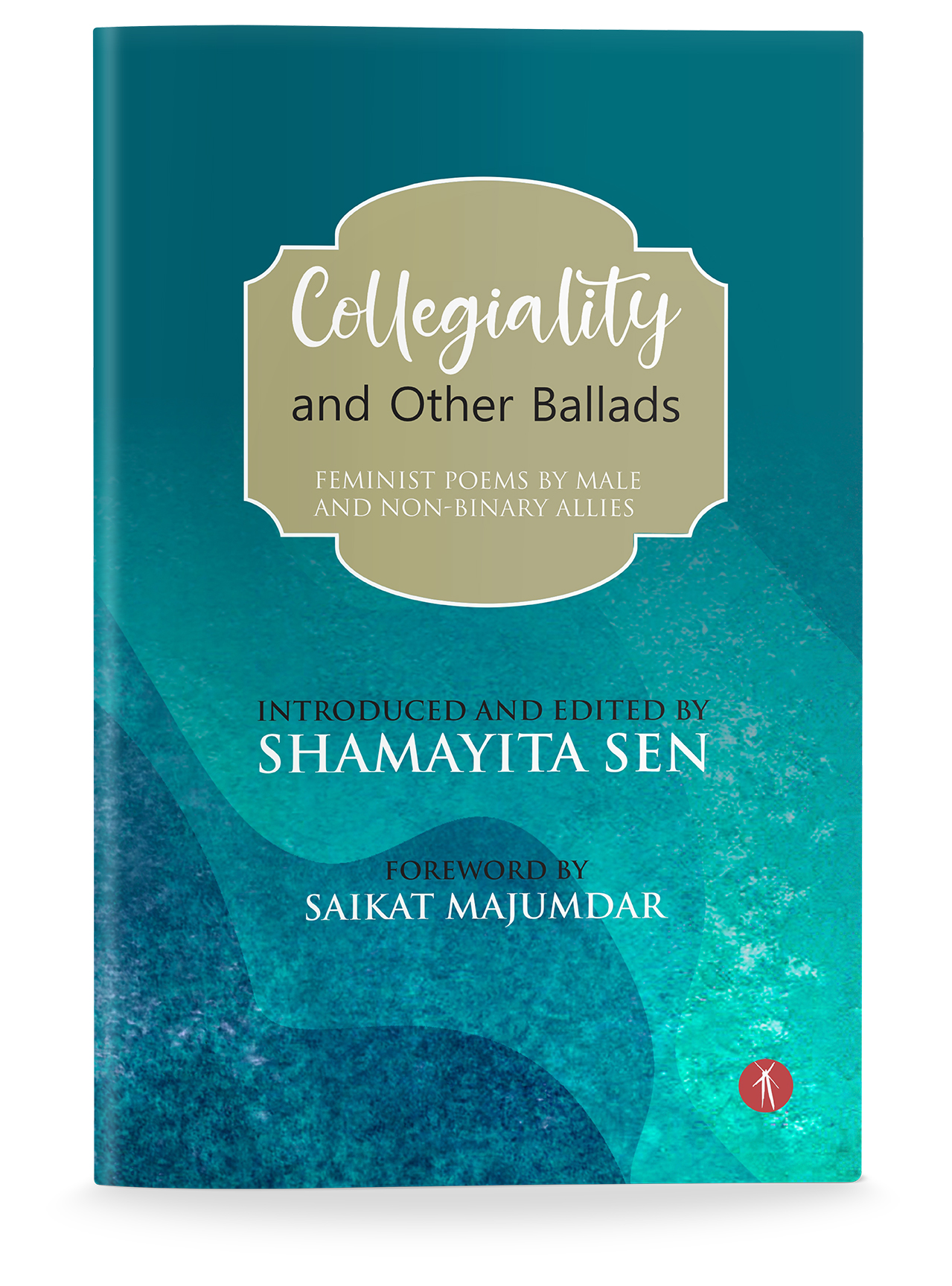

On Collegiality and Other Ballads: feminist poems by male and non-binary allies, edited by Shamayita Sen

Urvashi discusses one of the recent publications by Hawakal

Collegiality and Other Ballads is an object lesson. But, of course, men can do feminism. They must, or be content to let inequality prompt the flailing, lashing damage so many do learn to coolly and cruelly refer to as the human condition. They may do it badly, thrusting a frightened or revolted, lazy or greedy gaze out from a being they believe safe from the mucus and loam, which births and breeds them, mouthing “hooded sympathy” (48) or reimagining empathy as vivisection.

This book is also a challenge. Collegiality is the establishment of kinship between colleagues; it is to say I know what you mean, I extrapolate from this, which I have felt to name you thus, ma famille and familiar. Look out in this anthology, mainly, for that rare mythification which expands the life of its subject till she fills all the reader’s vision, then brings her back to form for you to recognize, unmistakably, in the hall, on the hill, at the reading. There are poets here who sashay into the line of fire and poets who efface themselves in tender homage to kin.

Editor Shamayita Sen says in her introduction, “To quantify social evolution, this anthology […] puts the onus onto (sic) those who are historically and structurally in socially privileged positions of power” (xiii). It meant then to explicitly publish what manner of solidarity, kinship, collegiality, men and non-binary allies have to offer womxn, their coworkers in feminism. Here is my selection of those to flip to.

The Old Woman’s Kitchen (40) perceives a parallel between the slow failure of an aging woman’s body and the habitual movements of her kitchen, connoted as her realm: her body politic ages and fails simultaneously with its sovereign.

Blue (41) is an example of a woman’s choice of self-representation being shaped by social circumstances.

Myth of the Baker’s Daughter (42) retells the Biblical story of Christ’s retributive metamorphosis of a baker’s daughter into an owl after she has denied him bread. The anonymous baker’s daughter is transformed into an owl of mythic proportions and character through the poet’s retelling.

Bringing Forth (44) narrates an alternative history of Eve — accidental mother to her nemesis, Adam.

Census (45) describes the impressions of enumerators who come to a “shelter for battered women […] to fill forms / to ask and record”— what they see and what they imagine of the women’s lives, bodies, and identities.

Lovers without Hands (46) speaks of touch as the time intersecting with space when desire approaches consummation. “Our story becomes landscape,” as the poet and their intimate (lover, other) arrive across it only to re-live and wait together.

An Ode to Woolf (47) imagines the inner life of an artist, her brushes with women, words, and men, her struggle with love, religion, and the normative she shies from as “average.” Prayer and plants are her allies, and when she “recalls the face of God; it is a woman.”

Trafficked (49) writes the abduction of women into slavery as the act of undress, sex, and seeding, at once attempting a rehabilitation of trafficked womanhood as mundane, and an ‘undressing’ of tillage and cultivation as a violation — violation retranslated or derived in its turn from that species of ‘rescue’ that tears and uproots, ‘screeches,’ ‘searches’ and ‘shames.’

The Day After (52) contrasts a mother’s representation of the Brahmaputra, whom her daughter weds, and of the “little stream […] who listens to her / and keeps all her secrets.”

On the Terrace (53) recalls a childhood exploration of uncharted territories and navigation around real and imagined monsters — bugs and bees, monkeys, piranhas, crocodiles. The poet and their ally encounter in the end one “more dangerous. / The height of your father, waiting” and name him “komodo dragon […] the friendly dinosaur next door.”

An Ode to Nightingales (55) is a play on Philomela — an acknowledgment of the ubiquity of domestic violence via a child’s evolving consciousness recognizing both his mother’s menstrual blood on a sanitary pad and her scars from being beaten by her husband his father.

Two Women (56) instances collegiality between woman and woman while referencing the victimization of women both in war and the ostensible peace of home through a coupling of the poet’s grandmother and a refugee at the Indo-Bangladesh border. The poet worlds a backdrop of the ungovernable — childhood, animal, woman.

My Gender (62) is a straight-up, exuberant reclamation of the poet’s gender as play and performance, inalienable and uncategorizable “baked in the oven of shame […] steeped in love, / warmth and utopian fantasies / that coalesce into collective aspirations.”

On Inter-Caste Love (64) is a commentary on the futility of marriage — the social(lly policed) contract between individuals, as well as that of languages.

Plus-Sized Poem (65) casts itself as a woman celebrating her body as free of constraints faced by lesser women. It tumbles between metaphors of self-love, repudiating standards of beauty and international prizes, refusal of censorship, and so on, in a fast-paced race to knock “the hourglass of time.”

Portrait of a Poet as a Young Woman (66) is a swaying, rhythmic reification of the young black or Dalit woman poet as word wizard, webbed onto the page through the imagery of flight, fire, hair, and hinge.

Fear of Lizards (84) invokes the banality of physical threat through single lines and nominal couplets that interrupt the blank pages of a woman’s sleep. The woman subject of the poem is beset by memory, past, and ever-present, as an audible drum of tiny monstrosities, alive.

Muslimah (104) presents six women’s resistance work in the first to the third person. The poet writes women who drive in Saudi Arabia, wear a hijab, present research on Aleppo, mother in Gaza, maintain a Youtube/Instagram channel on food, and do iconicity to educate girls globally.

Bride Wanted Ads (108) brings together ideas of cultural sexism, female infanticide, marriage as a conglomerate of market forces, and casteism in a compilation of ever-tightening control.

Conflict (109) is a woman declaring a sex strike till “government and rebel forces / settle for a peaceful stride.”

Gále (110) begins in an ungendered awareness of automation and assembly lines killing craft, heterogeneity, culture. “She meditates like a mountain” in the second stanza, the woman weaver, artist whose “nerves stretch through the universe.” The poetic voice is quietly stunned by the scope of her composition — to assimilate histories, preoccupations, aesthetics, movements. “She owns no war, stitches boundaries and / harvests the sun on her loom, / yet none of her children weave a gále.”

Grandpa and Grandma Sit on the Verandah (114) in a photograph that acts as a foil for grandpa’s poaching, his poor eyesight, and his fear of surviving his wife “the woman closest / to the sun” with her “crumpled skin that read like trashed paper.” There the “loftiness of slow lives / could, perhaps be discovered.”

Surviving Marital Rape (118) attempts to inhabit a woman’s consciousness as she is raped by a significant other.

Andro and Estro (121) might belong in an anthology of SFF poetry. Figurations of hormones meet for a drink, gossip and complain about binary-gendered folks, and are victimized by a rioting mob — “emasculated” and “stitched up” as the city’s men and women are too, “left as vague males and vague females,” self-fertilizing. Andro and Estro retreat to “an island named / Dopamine.”

On Tabassum, My Daughter, Stumbling Upon The Word ‘Consummation’ In A Dictionary (140) rejects a host of literary, religious, and poetic definitions/evocations of the word with the poet’s daughter — we do not know whether the “Not for her” that begins his versions of these evocations is her view or his, nor why. But the poem’s concluding lines flatten with the force of a sudden gust sweeping all preceding possibilities away. “For Her, / Consummatum est.” It is finished, as Christ said on his cross.

Urvashi V.

Editor, English language division, Hawakal

Browse Our Catalogue

- Bags2 products

- Bengali179 products

- Fiction40 products

- Journal2 products

- Memoir2 products

- Nonfiction42 products

- Poetry92 products

- English180 products

- Drama1 product

- Fiction27 products

- Journal3 products

- Literary Criticism6 products

- Memoir6 products

- Nonfiction19 products

- Poetry129 products

- Sanskrit1 product

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

Amazing works by our Country’s poets

Excellent compilation. A fabulous snapshot of the poetry scene

Wonderful book, a beautiful collection of poems. The book is a treat for the poetry lovers

Very good and informative book