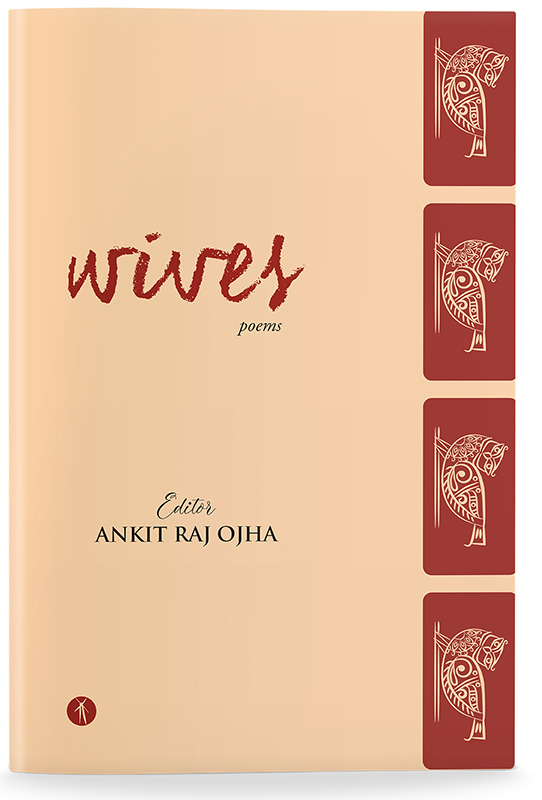

WIVES

I was at a wedding this monsoon, mouth full of delicious food and ears stuffed with brass band litany — an Indian staple when I received a text message from Hawakal about a literary project they wished to discuss with me. I sneaked out, dialled them with a hand over my uncommitted ear, and as the bride and groom took their oaths — younger cousins upholding tradition by hitting on prospective partners — the editor at Hawakal explained to me their idea of a poetry anthology meant for wives, by husbands.

Open to husbands — married, divorced, separated, estranged, and widowed — the anthology, while acknowledging and respecting all possible gender identities and husband-wife roles, seeks to present a selection of poetry penned by poets identifying as males, for female wives — theirs and others’. Our consideration does not disrupt, negate, or disrespect the relationships where a woman can be a husband to another woman, a man can be a wife to another man and other gender roles where traditional gender constructs are challenged.

One of our goals with this project was to make it diverse, both in form and content. I was elated to receive poems of many forms and genres — rhymed verse, free verse, prose poems, visual poems, sonnets, elegies, odes, satires, haiku, sequence poems, villanelles, and some that defy categorisation. Theme-wise, too, there is remarkable variety, notwithstanding the underlying theme that binds them all. In these poems, the reader lives the entire spectrum and many possibilities of marriage — sweet beginnings, bittersweet bickerings, everyday bliss, weary years, proud memories, tragic losses, doomed ends, and happily ever afters.

There is humour and play in Bob King’s depiction of conjugal life: “Bridget keeps confusing the words anecdote & antidote, which would be more maddening if I was bitten by a rattlesnake & hopping around on one foot” (“Lessons in Adaptability”).

In John Grey’s verse, we see husbands complemented and completed by wives: “My wife sips a martini, / doesn’t even notice the turbulence. / … I grip the armrests of my seat, / struggle to hold the plane together. / Any calmer and she’d be mistaken for / a Zen master meditating” (“The Calm One in a Rough Landing”).

In “Hummm,” D.C. Nobes captures the primordial vibration of companionship: “A chord of punctuation / in our swaying conversational hum / over the blend of mango and banana / strawberry and orange / with a hint of mint on the side. / I say “Hmmm!””

Nathanael O’Reilly offers comfort in metaphors: “You’re corduroy to my thighs. / You’re an afternoon nap and I’m jetlag” (“Epithalamium”).

Paul Hostovsky’s voice is the collective experience of many poet-husbands, as the wife in his poem commands: “If you write me another love poem, jeez, / keep me out of it, will you please? / … And it’ll be very good if I can read it / without a dictionary” (“Instructions for His Next Love Poem”).

Kiriti Sengupta treads the line between faith and superstition in his depiction of the boy-girl divide in Indian society:

Prior to her labor,

my mother-in-law keenly observed

my wife’s navel, Come on, it’s a boy!

…

My son is at school.

It’s a co-education convent.

After school, he tells his mother,

Girls sit on the left side. (“Y-Gene”)

And then in Sengupta’s portrayal of the male lifespan as a female liability: “She guards two pairs of bangles: / coral and conch. / Missus ensures they are intact. / She fears a chink will curtail my breath” (“Troth”).

Reliance on the better half is a recurring trope in the anthology. The husband in David Mihalyov’s poem depends on his spouse for his very memory: “He joins his daughters on the couch and scans / photo albums. Certain pictures elicit / events, but the printed versions / don’t match the cavities in his mind” (“Her Job is Not to be His Memory”).

In playful contrast to female liability, GJV Prasad bares the male burden in marriage: “my wife you wait / for my first faux pas of the day / being male and a husband / for me there is no escape” (“saturday morning ritual”). And he goes on to talk of promises kept: “I used to sing a Beatles song / About ageing together / Will you still need me / You reminded me / Singing / Now I am sixty-four / Still best friends” (“Wife”).

Formidable opponents populate Karan Kapoor’s verse that marries the domestic to the celestial:

Ma / kneads

dough / breaks her

nail / blames him

…

My father always stands

against the sky / even god

fails to compel his eye (“Rings of Saturn”)

While Steve Denehan gladly accedes to being the third wheel in his cosy alliance: “my wife smiles at my daughter / my daughter smiles back / I disappear for a moment / view it all as a ghost / as a person there but not there” (“Barcelona, October 2018”).

Amit Majmudar first teaches love and falling out in “Poem without a Title”: “A love with no fights is a pond with no tadpoles, / a poem with no rhymes, a church with no bibles. / … A love with no fights is a patient with no vitals”; and then in “Denial”: “The life left after a marriage is the silence left after the music.”

Roomy Naqvy’s verse, beginning in the safety of childhood, takes a grim turn: “As an infant, you loved soft toys, / Cuddly and silk-textured. / … Soft toys are nice and cuddly, / They are nice to hold, / They can kill you nicely” (“Soft Toys”).

Uday Shankar Ojha releases the skeleton in tradition’s closet: “Her glass eyes weaving mystery / piled dreams scarcely heard. / She wandered silently, running swift / and sudden when summoned” (“We Loved Not Each Other”). Then he goes on to narrate the turning of the tide: “She hisses and hushes / his words in the glottis. / Subversion of history lingers. / … She stamps defiant; / he slides softly” (“The Way the Wind Blows”).

We see a marriage marred by the banality of time in Richard-Yves Sitoski’s “Progress”: “Sinks remain full, the meals / we cook have fewer components. / … Our habits / are cardigans, see-through / at the elbows yet too tight to allow / the spreading of arms.”

And Sudeep Sen’s lament, a diptych spanning decades, bleeds poetic injustice:

We are sealed in marriage today

to celebrate

tomorrow — the earth’s longest day. (“Day Before Summer Solstice”)

Now, you carefully choose this day

to burn down that sacrament —

stardust to ash, ash to deathly black. (“Decree Nisi”)

These and more wonders dwell in these hundred or so pages, offering a fine selection from forty-seven poets (forty-eight, when I include mine) belonging to twelve countries. I’m blessed to have the support of these outstanding poets worldwide, just as I am grateful to Hawakal for trusting me with this project. I earnestly hope Wives reaches far and wide and serves its intended purpose of bringing joy and hope to those reading it.

Ankit Raj Ojha

15 October 2023

Karnal, Haryana

Browse Our Catalogue

- Bags2 products

- Bengali182 products

- Fiction40 products

- Journal2 products

- Memoir2 products

- Nonfiction44 products

- Poetry93 products

- English184 products

- Drama1 product

- Fiction27 products

- Journal3 products

- Literary Criticism6 products

- Memoir6 products

- Nonfiction20 products

- Poetry132 products

- Sanskrit1 product

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

Amazing works by our Country’s poets

Excellent compilation. A fabulous snapshot of the poetry scene

Wonderful book, a beautiful collection of poems. The book is a treat for the poetry lovers

Very good and informative book